Control as Inference

Tony Chen

19 Nov 2022

Life update: I’ve started grad school!

The goal of the next few posts will be to gradually build up to this paper here: planning as diffusion. In order to do so, I’ll need to fully build up some technical machinery along the way - we won’t be re-deriving everything from first principles, but will present the basic results necessary to understand the paper at a conceptual level. In this post, we’ll be covering an interesting reformulation of the reinforcement learning framework, by casting learning as inference in a very specially structured graphical model.

The Control as Inference Model

Our derivations will closely follow the original paper here , and I’ve also shamelessly stolen much of this exposition from another very helpful blog post here.

Essentially, our overarching goal is to find a way to re-formulate acting and control as performing inference in a graphical model. Why would we want to do this? Doing so will allow us to apply mature tools from PGMs and probability theory to reinforcement learning, and as we’ll briefly see later, will also provide a unifying framework for other approaches to RL such as Maximum Entropy RL.

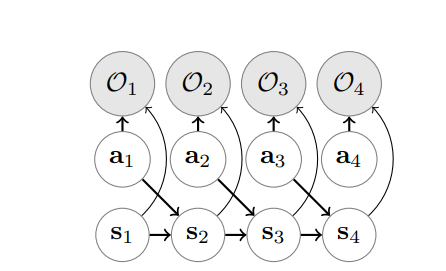

We’ll walk through the setup of the graphical model step by step. As with regular MDPs, we’ll let \(S\) denote the state space, \(A\) denote the action space, and \(T\) denote the transition distribution. What is different is how we handle reward in this graphical model. We’ll begin by introducing optimality variables \(o_t\), where \(o_t = 1\) if time step \(t\) is optimal, and 0 otherwise. What does it mean for a time step to be optimal, and how will this have anything to do with reward? We’ll unpack that next.

We’ll take the graphical model to have the following structure:

with the following conditional distributions:

\[p(a_t) \propto 1 \\ p(s_t \vert s_{t-1}, a_t) = T(s_t, a_t, s_{t-1}) \\ p(o_t = 1 \vert s_t, a_t) = \exp r(s_t, a_t)\]The naming of the function \(r\) is deliberately meant to be suggestive - we’ll see that this function has a natural connection to the notion of reward in an MDP. This can easily be explicated by considering the distribution over optimal trajectories \(\tau = (s_1,a_1,\ldots s_T,a_T)\):

\[\begin{align*}p(\tau \vert o_{1:T}) \propto p(\tau, o_{1:T}) &= p(s_1)\prod_t p(o_t\vert s_t,a_t)p(s_t\vert a_t,s_{t-1})\\&=\left[p(s_1)\prod_t p(s_t\vert a_t,s_{t-1})\right]\left(\prod_t p(o_t \vert s_t,a_t)\right)\\&=\left[p(s_1)\prod_t p(s_t\vert a_t,s_{t-1})\right]\exp \left(\sum_t r(s_t,a_t)\right)\end{align*}\]Note that if we take our dynamics to be deterministic, the term on the left drops out, and we have that the probability over a particular trajectory is proportional to the amount of reward earned along the way.

As with normal RL, our goal is to obtain a policy \(\pi\), a distribution over actions conditioned on our current state \(s_t\). Since we would like our policy to be reward maximizing, we’ll additionally condition our actions on them being optimal (\(o_t = 1\)), meaning that our objective is to compute \(\pi(s_t) = p(a_t \vert s_t, o_{1:T})\). We’ll compute this policy using sum-product, leading us to an algorithm that is broadly reminiscent of the forward-backward algorithm for HMMs.

Inference

To do so, we’ll compute both forward and backward messages to pass, starting with the latter. Our backwards messages will be of the form

\[\beta(s_t,a_t)=p(o_{t:T}\vert s_t,a_t),\\ \beta(s_t)=p(o_{t:T}\vert s_t)=\int_A \beta(s_t,a_t)p(a_t\vert s_t).\]We have that \(p(a_t \vert s_t) = \dfrac{1}{\vert A \vert}\), due to the prior \(p(a_t)\) also being uniform.

Because the messages factorize nicely through time, we can calculate them using a recursive procedure, exploiting the following factorization (relying on the fact that \(o_t \perp s_{t+1} \vert s_t\):

\[\beta(s_t,a_t)=\int_S \beta(s_{t+1})p(s_{t+1}\vert s_t,a_t)p(o_t \vert s_t, a_t).\]With this in hand, we are now ready to compute our policy. We have that:

\[\begin{align*}p(a_t \vert s_t,o_{1:T})&=p(a_t \vert s_t,o_{t:T})=\frac{p(o_{t:T}\vert s_t,a_t)p(a_t\vert s_t)}{p(o_{t:T}\vert s_t))}\\&=\frac{\beta(s_t,a_t)}{\beta(s_t)}. \end{align*}\]Ok, so we have our answer to the question of how we compute the policy. But what does the ratio look like, and does it match our expectations from classical RL for how a policy should behave?

Let’s take a look at the messages again. Let

\[Q(s_t,a_t)=\log\beta_t(s_t,a_t)\\V(s_t) = \log \beta_t(s_t).\]We can see that

\[\begin{align*}Q(s_t,a_t) &= \log p(o_t \vert s_t, a_t)\int_S \beta(s_{t+1},a_{t})p(s_{t+1}\vert s_t,a_t)\\ &= r(s_t,a_t) + \log \mathbb{E}_{s_{t+1} \sim p(s_{t+1} \vert s_t, a_t)}\left[ \beta_t(s_{t+1})\right] \\ &= r(s_t,a_t) + \log \mathbb{E}\ \exp V(s_{t+1}),\\ V(s_t) &= \log \mathbb{E}_{a_t}\ Q(s_t, a_t). \end{align*}\]If we think of \(\log \mathbb{E}\ \exp f(x) \approx \max f(x)\) as a “soft maximum” operator, then we can see that the equations for Q and V are “soft” analogues of the bellman backup operator, where we first take a soft maximum over actions, and then a soft maximum over states.

Reformulated this way, we can see that our policy selects an action proportional to the advantage function:

\[p(a_t \vert s_t,o_{1:T}) = \exp(Q(s_t,a_t)- V(s_t))=\exp A(s_t,a_t).\]Maximum Entropy Reinforcement Learning

We’ll use the work we’ve just done to derive another way to approximate to this policy, which will lead us to a closely related framework often termed as Maximum Entropy Reinforcement Learning. To start with, we’ll use a variational approximation to the trajectory, so we’ll be working in an optimization setting.

Recall our distribution over trajectories, conditioned on their optimality:

\[p(\tau \vert o) = \left[p(s_1)\prod_t p(s_t\vert a_t,s_{t-1})\right]\exp \left(\sum_t r(s_t,a_t)\right).\]We can also equivalently rewrite it as:

\[\begin{align*}p(\tau \vert o) &\propto p(s_1 \vert o)\prod_t p(a_t \vert s_t, o)p(s_{t} \vert s_{t-1},a_t, o)\\ &=\left[p(s_1 \vert o)\prod_t p(s_{t} \vert s_{t-1},a_t,o)\right]\left(\prod_t \pi(a_t\vert s_t)\right),\end{align*}\]by using bayes’ rule in the other direction instead. In this way, we can see that our policy \(\pi\) is a variational approximation to \(p(\tau)\) in the case of deterministic dynamics, in the sense that if set up our variational approximation \(q(\tau)\) to be:

\[p(\tau \vert o)=\underbrace{\mathbb{1}(p(\tau) \neq 0)}_{\text{ensure the traj is consistent}}\left(\exp\sum r( s_t,a_t)\right),\\q(\tau) = \mathrm{1}(p(\tau) \neq 0)\left(\prod_t \pi(a_t\vert s_t)\right),\]then \(\pi(a_t \vert s_t) = p(a_t \vert s_t, o)\) is the unique distribution such that \(D_{KL}(q(\tau) \vert\vert p(\tau)) = 0\).

But, this is not the case in stochastic dynamics, since we have that \(p(s_{t} \vert s_{t-1},a_t,o) \neq p(s_{t} \vert s_{t-1}, a_t)\) generally. Thus those two distributions differ in a way that is not just due to \(\pi\), and solving the variational approximation requires simultaneously approximating the reward distribution and the transition distribution. The solution to this problem is basically what you would expect, which is to force the posterior transition dynamics to conform to the true dynamics, i.e. forcing \(p(s_{t} \vert s_{t-1}, a_t, o) = p(s_{t} \vert s_{t-1}, a_t)\). In that case, our variational approximation becomes:

\[q(\tau) = \left[p(s_1)\prod_t p(s_t\vert a_t,s_{t-1})\right]\left(\prod_t \pi(a_t \vert s_t)\right).\]Our objective is to find a function \(\pi(a_t \vert s_t)\) that maximizes the negative divergence \(-D_{KL}(q(\tau) \vert\vert p(\tau))\) - which is equivalent, up to an additive constant, to maximizing the ELBO:

\[\begin{align*}-D(\hat{p}(\tau) \vert\vert p(\tau)) &= \int q(\tau) \log \frac{p(\tau)}{q(\tau)}\\ &= \int q(\tau)\left[\sum_t r(s_t,a_t) - \log \pi(a_t \vert s_t) \right] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim q} \left[\sum_t r(s_t,a_t) - \log \pi(a_t \vert s_t) \right] \\ &= \sum_t \mathbb{E}_{(s_t,a_t) \sim \hat{p}(s_t,a_t)}\left[ r(s_t,a_t) - \log \pi(a_t \vert s_t) \right] \\ &= \sum_t \mathbb{E}_{(s_t,a_t)} \left[ r(s_t,a_t)\right] + \mathbb{E}_{s_t} [\mathcal{H}\pi(a_t \vert s_t)],\end{align*}\]where \(\mathcal{H}\) is the entropy of a distribution. This is where the term maximum entropy comes from: minimizing the KL is equivalent to maximizing negative KL, which in turn is equivalent to maximizing reward gained as well as the conditional entropy of the action.

We’ll work the optimization process iteratively, by first finding the optimal \(\pi(a_T \vert s_T)\), and then backing up to the initial time step. The base case is a pretty standard derivation:

\[\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}_{(s_T,a_T)}&\left[r(s_T,a_T)- \log \pi(a_T \vert s_T)\right] \\&= \mathbb{E}_{(s_T,a_T)}\left[r(s_T,a_T)-\log \pi(a_T \vert s_T) + V(s_T) - V(s_T)\right] \\ &=\mathbb{E}_{(s_T,a_T)}\left[\frac{\exp r(s_T,a_T)}{\exp V(s_T)}-\log \pi(a_T \vert s_T) + V(s_T)\right] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{s_T}\left[-D_{KL}\left(\pi \vert\vert \frac{\exp r(s_T,a_T)}{\exp V(s_T)}\right) + V(s_T)\right],\end{align*}\]and it’s clear to see that this is maximized when \(\pi(a_T \vert s_T) = \exp(r(s_T,a_T) - V(s_T))\) (note that we are analogously defining \(V(s_t) = \log \int_A \exp r(s_t,a_t)\)).

For the inductive case, there are some subtleties that we have to take care of: in particular, changing \(\pi\) for time T will have a cascading effect on all of the expectations for \(t < T\). More specifically, setting \(\pi(a_T \vert s_T)\) according to the above reduces the term to \(\mathbb{E}_{s_T}\left[V(s_T)\right]\), meaning that for \(T - 1\), we must maximize

\[\mathbb{E}_{(s_T,a_T)}\left[r(s_T,a_T)- \log \pi(a_T \vert s_T) + \mathbb{E}_{s_T}\left[V(s_T)\right]\right],\]instead. (Why? Well, implicit in the \(\mathbb{E}_{s_T}\) is the fact that this expectation is with respect to the distribution \(p(s_T \vert s_{T-1}, a_{T-1})\)! This means that we cannot drop this term as a constant in our optimization, since it actually depends on \(s_{T-1}\)).

Thus, the general inductive case proceeds by optimizing

\[\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}_{(s_t,a_t)}&\left[r(s_t,a_t)- \log \pi(a_t \vert s_t) + \mathbb{E}_{s_{t+1}}\left[V(s_{t+1})\right]\right]\\ &= \mathbb{E}_{s_t,a_t}\left[D_{KL}\left(\pi \vert\vert \frac{\exp Q(s_t,a_t)}{\exp V(s_t)}\right) + V(s_t)\right],\end{align*}\]where analogously,

\[Q(s_t,a_t)=r(s_t,a_t)+\mathbb{E}_{s_{t+1}}\left[V(s_{t+1})\right].\]Thus, the general policy is given by

\[\pi(a_t \vert s_t) = \exp (Q(s_t,a_t)-V(s_t))\]as before, with the key difference being that the Q function is now an expectation rather than a soft max, while the V function remains a softmax from before. This is mostly a good thing - replacing a soft max with an expectation causes the policy to be less blindly optimistic when exploring future states.

Conclusion

Control as Inference is a fun little paradigm to reformulate our classical view of reinforcement learning from a traditional reward maximizing framework into an inferential, probabilistic framework. We saw that it led to some nice “relaxed” analogs of our traditional dynamic programming solutions to MDPs, and while they may not be heavily used in practice, this framework will prove to be invaluable once we start talking about how to integrate diffusion models (which are heavily probabilistic) with planning, in the next few posts. Stay tuned!