State Space Models of Classical Conditioning

Tony Chen

18 Dec 2019

Since all of my posts have been about theory and methods, I’d like to take some time to describe some applications. And, because I’m a psychology major, I’d like to give a very brief example about how probailistic models are applied to psychology or neuroscience. In particular, I will focus on one class of models - linear state space models, and one application - modeling associative learning using Rescorla Wagner learning dynamics. This blog post derives from a paper I read by Sam Gershman - you can find it here.

- State Space Models

- Kalman Filters

- The Rescorla Wagner Model

- A Probabilistic Formulation

- Implementation

State Space Models

State Space Models are probabilistic models of physical systems that evolve through time. In general, these models have two components - the underlying, true latent representation, and the observed measurements, which are noisy observations of the underlying system. What separates a SSM from a simple measurement model or latent variable model, is that the value of the variables evolve through time. This makes performing inference on the hidden states more challenging than a normal latent variable model.

More formally, denote by \(z_t\) the hidden variables of the system, and by \(y_t\) the observations of the system. A state space model posits the following relationship between the hidden and observed variables:

\[z_t = g(z_{t-1}, \epsilon_t), \; y_t = h(z_t, \eta_t).\]Above, \(\epsilon_t\) and \(\eta_t\) are the error variables, and we endow them with multivariate gaussian distributions with error covariances \(Q \text{ and } R\):

\[\epsilon_t \sim N(0, Q_t), \; \eta_t \sim N(0, R_t).\]Again, I’ll emphasize that the value of \(z_t\) depends on \(z_{t-1}\), its value at the previous time step.

Now, the most common assumption to make is that the \(g\) and \(h\) functions are linear, meaning that our state space model now takes the following form:

\[z_t = A_t z_{t-1} + \epsilon_t, \; y_t = C_t z_t + \eta_t,\]where \(A_t, C_t\) are weight matrices. For the purposes of this post, I will assume that all parameters \(Q_t, A_t, C_t, R_t\) are stationary, meaning that they do not depend on time. As such, from now on, I’ll drop the t subscript when talking about the weight matrices.

The final step of the model is to specify an initial distribution for our hidden state. In this post, I’ll assume that the hidden states are gaussian distributed:

\[z_0 \sim N(\mu_0, \Sigma_0) .\]With this linear assumption, our state space model now becomes what is commonly called a linear dynamical system. As we will see, this assumption makes the model tractable, and allows for exact posterior inference on the hidden states \(z_t\).

The Kalman Filter

With a SSM, the most common objective is to draw inferences on the posterior distributions of the hidden states conditioned on the observations:

\[p(z_t | y_{1:t})\]The Kalman Filter is a recursive algorithm that allows us to exactly compute the posterior distribution above. We can conceptualize it as a two stage process: predict, and update.

In the predict step, we use the a posteriori estimate of the previous state to estimate the current hidden state, and in the update step, we combine our predicted estimate with information from the observed state to obtain the a posteriori estimate of the current time step.

We formalize the above description as follows. Define \(\hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1}\) to be the posterior expectation of state \(z_t\), conditioned on the first \(t - 1\) observations (although only the \(t - 1\) observation actually matters, due to the markov property of this system). Similarly, define \(P_{t \vert t - 1}\) to be the covariance of the error \(z_t - \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1}\) - since \(\hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1}\) is a constant, this is also the covariance of \(z_t\) conditioned on observations \(y_{t - 1}\).

And, I’ll also go ahead and define the alternate notation \(\mu_t = \hat{z}_{t \vert t}, \; \Sigma_t = P_{t \vert t}\); we won’t use it in the derivation, but I will use it later.

Our objective is \(\hat{z}_{t \vert t}\), which we calculate using the predict and update steps.

In the predict step, we calculate \(\hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1}\) from \(\hat{z}_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}\), by using the linear equation specified by our SSM:

\[\hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1} = \mathbb{E}_{z_t \vert y_{t-1}}[z_t] = \mathbb{E}_{z_{t - 1} \vert y_{t-1}}[Az_{t-1} + \epsilon] = A\hat{z}_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}\]This naturally follows because the \(\epsilon\)s have mean 0. To derive the error covariance matrix, we simply expand out the definitions:

\[\begin{align*} P_{t \vert t - 1} &= Cov(z_t - \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1}) \\ &= Cov(Az_{t-1} + \epsilon_t - A\hat{z}_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}) \\ &= Cov(A(z_{t-1} - \hat{z}_{t - 1 \vert t - 1})) + Cov(\epsilon) \\ &= AP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T + Q \end{align*}\]Note that above, we could also split the covariance of the sum, because of the independence assumption we imposed on \(\epsilon_t\) and \(z_t\).

Let’s recap what we’ve done here. We’ve found the posterior mean and covariance of \(z_t\) conditioned on \(y_{t - 1}\), which we expressed in terms of the posterior mean and covariance of \(z_{t-1}\) conditioned on \(y_{t - 1}\). And, because we know that \(z_t \vert y_{t - 1}\) is a gaussian random variable, since gaussians are closed under addition and scaling, we can conclude that

\[z_t \vert y_{t - 1} \sim N(A\hat{z}_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}, AP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T + Q)\]But, that’s not all of the information we have! We’d like to take into account our current observation \(y_t\) as well, which is the update step of the filter.

So, let \(\hat{y}_t = C\hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1}\) be the expected value of \(y_t\) under our predicted value of \(z_t\). Define the measurement residual as

\[\delta_t = y_t - \hat{y}_{t| t - 1}.\]The measurement residual gives us a measure of how far off our prediction was from the actual observed value. Now, we assume that the posterior estimate is given by a linear combination of our predicted estimate \(\hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1}\) and the measurement residual. This comes from the fact that if our guess is wildly off target, we should update our estimate of the hidden state more to compensate.

Thus, our updated estimate takes the form

\[\hat{z}_{t \vert t} = \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1} + K_t \delta_t,\]where \(K_t\) is some learning rate or weight that we give to the residual - we’ll derive the optimal form of \(K_t\) below.

In addition, we can also calculate the covariance of our measurement error \(\delta_t\) - call this \(S_t\) - in an analogous fashion as our calculation for \(P_{t \vert t - 1}\).

\[\begin{align*} S_t &= Cov(\delta_t) = Cov(y_t - \hat{y}_{t | t - 1}) \\ &= Cov(Cz_t + \eta_t - C\hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1}) \\ &= CCov(z_t - \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1})C^T + Cov(\eta_t) \\ &= CP_{t \vert t - 1}C^T + R \end{align*}\]The next step, before we derive \(K_t\), is to calculate the update for the error covariance matrix \(P_{t \vert t}\). We can do this again by some rote simplification:

\[\begin{align*} P_{t \vert t } &= Cov(z_t - \hat{z}_{t \vert t}) \\ &= Cov(z_t - (\hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1} + K_t \delta_t)) \\ &= Cov(z_t - (\hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1} + K_t(y_t - C\hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1} ))) \\ &= Cov(z_t - \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1} - K_t (Cz_t + \eta_t - C\hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1})) \\ &= Cov(z_t - \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1} - K_t C(z_t - \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1}) - K_t \eta_t) \\ &= Cov((I - K_tC)(z_t - \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1}) - K_t \eta_t) \\ &= Cov((I - K_tC)(z_t - \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1})) - Cov(K_t \eta_t) \\ &= (I - K_t C)P_{t \vert t - 1}(I - K_t C)^T + Cov(K_t \eta_t) \\ &= (I - K_t C)P_{t \vert t - 1}(I - K_t C)^T + K_t R K_t^T \end{align*}\]Above, we have again used the fact that \(z_t\) and \(\eta_t\) are independent. Furthermore, we know that \(\eta_t\) is symmetric around 0, meaning that \(Cov(K_t \eta_t) = - Cov(K_t \eta_t)\).

From this, we can finally derive the optimal form of \(K_t\).

Here’s our objective. We want to find \(K_t\) that minimizes the expected squared error of our hidden states vs our predicted hidden states:

\[\mathbb{E}[(z_t - \hat{z}_{t \vert t})^2].\]Note that this is precisely the trace of the matrix \(P_{t \vert t}\). So, lets begin by completely expanding out the formula for \(P_{t \vert t}\):

\[\begin{align*} P_{t \vert t} &= (I - K_t C)P_{t \vert t - 1}(I - K_t C)^T + K_t R K_t^T \\ &= (I - K_t C)(AP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T + Q)(I - K_t C)^T + K_t R K_t^T \\ &= (AP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T + Q - K_tCAP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T - K_tCQ)(I - K_t C)^T + K_t R K_t^T \\ &= \left(AP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T + Q - K_tCAP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T - K_tCQ - AP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T(K_tC)^T - Q(K_tC)^T\right. \\ &\qquad \left. + K_tCAP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T(K_tC)^T + K_tCQ(K_tC)^T + K_t R K_t^T\right) \\ &= P_{t \vert t - 1} - K_tCP_{t \vert t - 1} - P_{t \vert t - 1}(K_tC)^T + K_tCP_{t \vert t - 1}(K_tC)^T + K_t R K_t^T \\ &= P_{t \vert t - 1} - K_tCP_{t \vert t - 1} - P_{t \vert t - 1}(K_tC)^T + K_t(CP_{t \vert t - 1}C^T + R)K_t^T \\ &= P_{t \vert t - 1} - K_tCP_{t \vert t - 1} - P_{t \vert t - 1}(K_tC)^T + K_tS_tK_t^T \end{align*}\]Now, we want the trace of this matrix to be minimized. Recall that the trace is linear, meaning that

\[Tr(P_{t \vert t}) = Tr(P_{t \vert t - 1}) - Tr(K_tCP_{t \vert t - 1}) - Tr(P_{t \vert t - 1}(K_tC)^T) + Tr(K_tS_tK_t^T).\]Take the derivative of the above expression with respect to \(K_t\), and set equal to 0 to get

\[0 = -(CP_{t \vert t - 1})^T - P_{t \vert t - 1}C^T + 2K_tS_t = -2(CP_{t \vert t - 1})^T + 2K_tS_t.\]Re-arrange, and solve for \(K_t\):

\[K_t = P_{t \vert t - 1}C^TS_t^{-1}.\]Because \(P_{t \vert t - 1}\) is a covariance matrix, it is symmetric, which is why we can just drop the transpose. And thus, we have our optimal \(K_t\), which we commonly call the kalman gain.

With this, we have fully specified the kalman filter.

But, we’re not quite finished yet.

Note that now that we have derived our optimal \(K_t\), we can go back and simplify our ugly expression for \(P_{t \vert t}\) earlier.

Indeed, if we multiply the upper equation on both sides by \(S_tK_t^T\), we find that

Thus, an extra term cancels out in the derivation, giving us

\[P_{t \vert t} = P_{t \vert t - 1} - K_tCP_{t \vert t - 1}\]as our final answer.

Just to recap, the kalman filter is a recursive algorithm where we first predict the hidden state from our previous time estimate, and then update our prediction with the measurement residual to obtain the fully posterior expectation of our hidden state, conditioned on our observation history.

And, to put the whole thing in probabilistic terms, we have a closed form expression for our posterior distribution of \(z_t\):

\[\begin{align*} z_t \vert y_t &\sim N(\hat{z}_{t \vert t}, P_{t \vert t}) \\ &= N(A\hat{z}_{t - 1 \vert t - 1} + K_t\delta_t, P_{t \vert t - 1} - K_tCP_{t \vert t - 1}) \\ &= N(A\hat{z}_{t-1} + K_t \delta_t, AP_{t - 1 \vert t-1}A^T + Q - K_tC(AP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T + Q)). \end{align*}\]The Rescorla Wagner Model

The Rescorla Wagner model was one of the first computational models that aimed to formalize the process of how we learn. It’s significant not just as a novel computational model, but also because it started the field of reinforcement learning, which is a significant branch of machine learning today.

The main idea is this: humans learn by prediction errors, which are discrepancies between what we expect, and what we actually get in response to some stimulus.

Suppose that you really love ice cream, but you have no idea what an ice cream truck is. And one day, you hear the music of an ice cream truck, go outside to check what the noise is, and stumble upon the ice cream truck! You leave the truck with an ice cream cone, incredibly pleased with yourself.

What did you expect when you heard the music? Most likely nothing special. However, you instead got ice cream, which is a positive outcome! Thus, you would have a positive prediction error, since the result you received from the world was much better than the result you were expecting.

This works analogously in the negative setting as well - suppose you heard the ice cream music again, and went outside, but it was a salad truck, playing ice cream music to trick you into going outside. In that case, you would have a negative prediction error (unless you really like salad and really dislike ice cream).

Now, how do we formalize this notion of predictive errors? To do this, I’ll first introduce some basic definitions. Keep in mind that there’s a lot being glossed over, for the sake of brevity. The first concept is that of a stimulus. In our example, the ice cream truck music would be the stimulus (more technically, the conditioned stimulus); this is some cue from the outside world. Then, we have some value that we associate to the stimulus

Let \(r_t\) denote the result from the world at the tth time step - in a psychology experiment, this would be the tth trial, and in our example, this would be the tth time you heard the ice cream truck music. For simplicity, we assume it takes three values - -1, 0, 1 for negative, neutral, and positive results, respectively. Let \(v_t\) denote the value that you associate to the stimulus (ice cream music) at time step t.

The Rescorla Wagner model posits that your value at time \(t + 1\) is governed by the magnitude of the difference between what you expect and what you got:

\[v_{t + 1} = v_t + \alpha (v_t - r_t)\]The \(v_t - r_t\) term represents our prediction error, and is typically denoted by \(\delta_t\)

This formulation lends itself well to a generalization to multiple stimuli. Suppose now that we have multiple stimuli that we are training; but crucially, only one is active at any given trial. In that case, we can introduce a one hot encoded vector \(x_t\), with zeros everywhere except in the position of the active stimulus on trial t. Our value \(v_t\) is now also a vector, with the same dimensionality as \(x_t\). Therefore, the model equation becomes:

\[v_{t + 1} = v_t + \alpha x_t(v_t - r_t)\]Notice that only the value corresponding to the active stimulus (the entry of \(x_t\) that is a one) is updated at trial t.

A Probabilistic Formulation of the Rescorla Wagner Model

If we take a step back and stare at the above equation for a while, we notice something interesting. This update for \(v_t\) looks exactly like the posterior mean for the latent state of a state space model!

Let me clarify this a bit more. Take our state space model from the first section, and set the equivalences:

\[v_t = z_t, \; r_t = y_t, \; A = I, \; C_t = x_t^T\]Notice that the \(C\) matrix is no longer time-homogenous, since it depends on \(t\); this is no big deal, since the updates are exactly the same. Our state space model then becomes

\[v_t = v_{t - 1} + \epsilon, \; r_t = x_t^Tv_t + \eta\]The next thing to do is to specify the error covariance matrix of \(\epsilon \text{ and } \eta\):

\[Cov(\epsilon) = \tau^2 I, \; Cov(\eta) = \sigma^2 I.\]Finally, the only thing left to do is to specify the initial distribution of \(v_t\), which we do so as

\[v_0 \sim N(0, \sigma_0^2 I).\]The crucial difference between this formulation and the rescorla wagner model is that here, the values and rewards are random variables. That way, we specify an entire distribution over the value we assign to a stimulus, which allows us to better quanitfy the uncertainty in our decisions.

However, as we will soon see, both formulations lead to almost identical update equations.

Begin by supposing that \(v_{t - 1} \vert r_{t - 1} \sim N(\mu_{t-1}, \Sigma_{t - 1})\); or in terms of our previous notation,

\[\hat{v}_{t - 1 \vert t - 1} = \mu_{t - 1}, \; P_{t - 1 \vert t - 1} = \Sigma_{t - 1}.\]Now, lets re-formulate the kalman updates. Begin by recalling our kalman gain update:

\[K_t = P_{t \vert t - 1}C^TS_t^{-1} = (AP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T + Q)C^T(CP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}C^T + R)^{-1}.\]If we replace this with our new notation, we have

\[K_t = (\Sigma_{t - 1} + \tau^2I)x_t(x_{t-1}^T\Sigma_{t - 1}x_{t-1} + \sigma^2I)^{-1}.\]Next, recall our posterior variance update. We have that

\[P_{t \vert t} = P_{t \vert t - 1} + K_tCP_{t \vert t - 1} = AP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T + Q + K_tC(AP_{t - 1 \vert t - 1}A^T + Q).\]This becomes

\[\Sigma_t = \Sigma_{t - 1} + \tau^2I + K_tx^t(\Sigma_{t - 1} + \tau^2I).\]Finally, we have our posterior mean update.

\[\hat{z}_{t \vert t} = \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1} + K_t \delta_t = \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1} + K_t (y_t - \hat{z}_{t \vert t - 1}) = A\mu_{t - 1} + K_t(y_t - A\mu_{t - 1}).\]repeating the same process lets us see that the posterior mean of \(v_{t + 1}\) conditioned on \(r_{t + 1}\) is

\[\mu_t = \mu_{t - 1} + K_t(\mu_{t - 1} - r_{t - 1}).\]This looks almost identical to the Rescorla Wagner update, with the key exception that our learning rate, now given by \(K_t\), varies with time instead. So, to summarize, our probabilistic version of the Rescorla Wagner model is governed by the following equations:

\[K_t = (\Sigma_{t - 1} + \tau^2I)x_t(x_{t-1}^T\Sigma_{t - 1}x_{t-1} + \sigma^2I)^{-1}.\] \[\Sigma_t = \Sigma_{t - 1} + \tau^2I + K_tx^t(\Sigma_{t - 1} + \tau^2I).\] \[\mu_t = \mu_{t - 1} + K_t(\mu_{t - 1} - r_{t - 1}).\]Implementation

Finally, let’s implement this algorithm and test it out on a toy problem to see if it works. All we need to do is implement the formula for the kalman gain, and the mean/variance update equations.

import numpy as np

class Filter:

"""

State Space model that models the trial-level reward process

"""

def __init__(self, n_states, n_trials, tau, sigma, cov_init = None):

self.n_states = n_states

self.n_trials = n_trials

self.cov_init = cov_init

# weights refer to the mean value associated with each stimulus

self.weights = np.zeros((n_trials, n_states))

self.cov = np.zeros((n_trials, n_states, n_states))

if cov_init:

self.cov[0] = cov_init

else:

self.cov[0] = np.diag(np.ones(n_states))

self.tau_sq = np.power(tau, 2)

self.sigma_sq = np.power(sigma, 2)

def train(self, rewards, stimuli):

tau_diag = np.diag(np.repeat(self.tau_sq, self.n_states))

for t in range(self.n_trials - 1):

x_t = stimuli[t]

delta_t = rewards[t] - self.weights[t]

# numerator of kalman gain. save as variable for reuse

gain_tmp = np.dot((self.cov[t] + tau_diag), x_t)

gain_t = gain_tmp / (np.dot(gain_tmp, x_t) + self.sigma_sq)

self.weights[t + 1] = self.weights[t] + gain_t * delta_t

self.cov[t + 1] = self.cov[t] + tau_diag - np.dot(gain_t, gain_tmp)

Then, let’s give the model a very simple task. We’ll have one stimulus, that always results in a reward of one.

if __name__ == "__main__":

n_states = 1

n_trials = 100

rewards = np.ones(n_trials)

stimuli = np.ones(n_trials)

test = Filter(n_states, n_trials, .01, 1)

test.train(rewards, stimuli)

Lets see the result

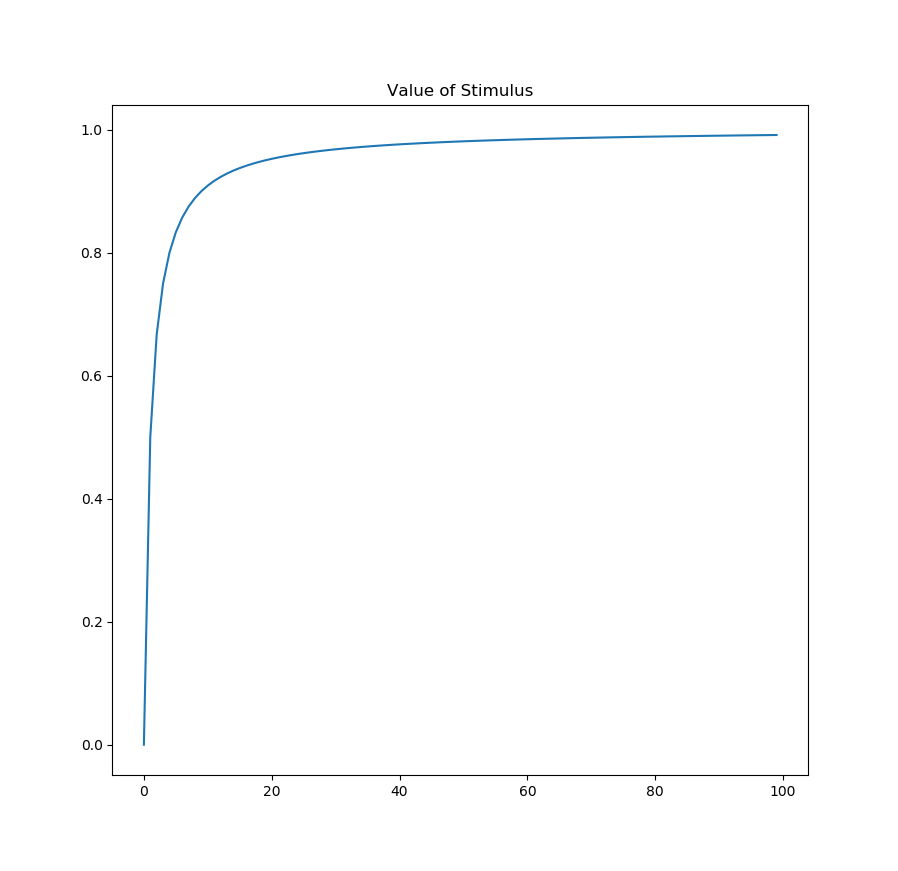

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(test.weights)

ax.set_title("Value of Stimulus")

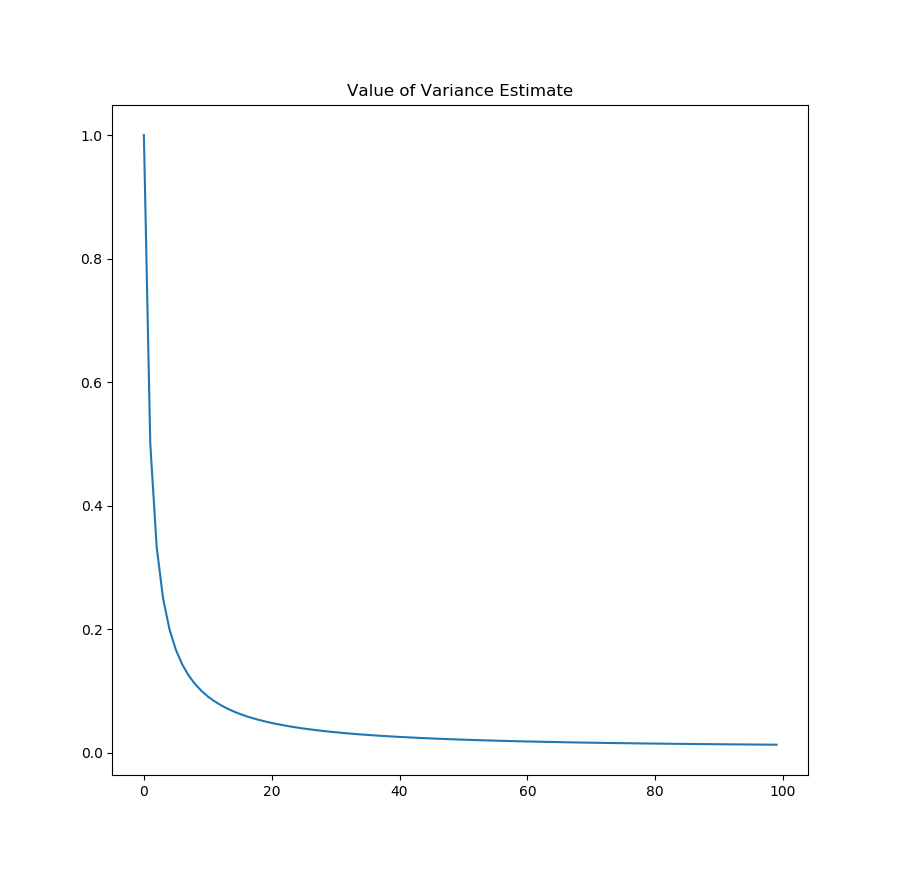

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(test.cov.squeeze())

ax.set_title("Variance of Value")

As you can see, not only do we converge to the true value of the stimulus, the variance in our estimate also goes down as we observe more data. Now, obviously this is a toy problem, but as shown in the paper I linked at the beginning, re-interpreting the Rescorla Wagner model in a probabilistic sense allows us to explain many psychological phenomena that the original model fails to account for.

I hope I’ve given a very brief overview of how statistical models can be used not just to analyze data, but to actually model psychological behavior. We looked at the class of linear state space models, and saw how the update equations for these models very closely paralleled how humans actually process stimuli and learn from reward. Now, obviously, this model is pretty simplistic, and the field of reinforcement learning in psychology has come a long way since Rescorla and Wagner, but I still thought that it was quite impressive that such a simple model could accurately describe such a complicated behavior process.